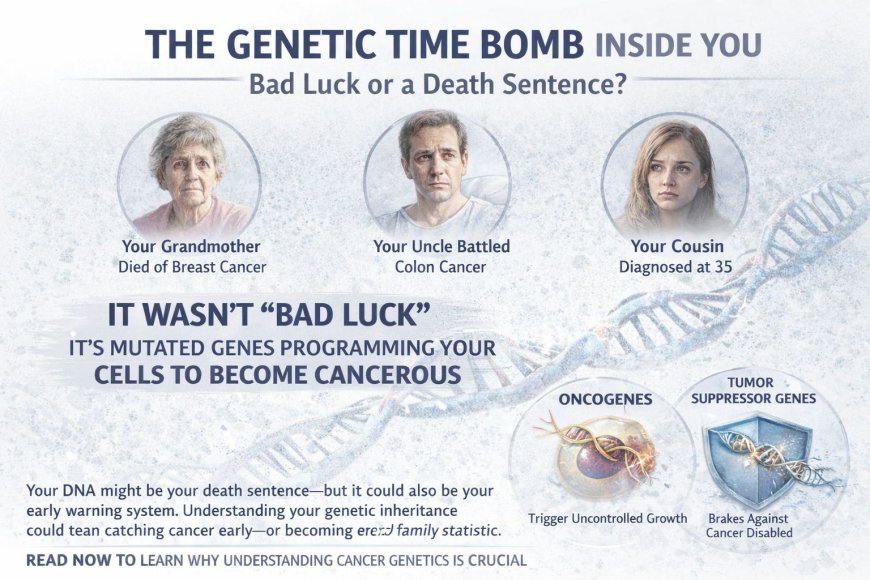

The Genetic Time Bomb Inside You: Why Your Family's "Bad Luck" With Cancer Isn't Luck at All

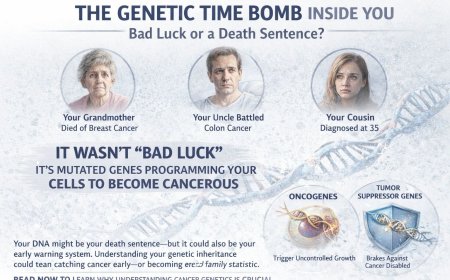

Your grandmother died of breast cancer. Your uncle battled colon cancer. Your cousin just got diagnosed at 35. Everyone says it's bad luck. Wrong. You're carrying mutated genes programming your cells to become cancerous. While you think "it won't happen to me," those genetic time bombs are ticking. This article reveals the brutal science of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes—the genetic switches controlling whether you get cancer or not—and why understanding your genetic inheritance could be the difference between catching cancer early or becoming the next family statistic. Your DNA might be your death sentence, but it could also be your early warning system.

The Moment Your Genetics Became a Death Sentence (And You Don't Even Know It)

Picture this:

You're at a family wedding. Third cousin Meera just announced her breast cancer diagnosis. She's 38. Everyone's whispering. "Another one." Your aunt whispers, "It's in the family. Nothing we can do."

You nod sympathetically. You're 32. You feel fine. Healthy. Strong.

But here's what you don't know:

Right now, inside the nucleus of billions of your cells, there are genes — oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes — that are either protecting you from cancer or actively creating it.

And if cancer "runs in your family," there's a meaningful chance you've inherited mutated versions of these genes.

You might be carrying a broken BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, which dramatically elevates breast and ovarian cancer risk. Or a damaged TP53 gene associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Or a mutated APC gene linked to colon cancer. Or faulty MLH1 or MSH2 genes associated with Lynch syndrome — a hereditary condition that raises the risk of colon, endometrial, and other cancers.

These aren't "bad luck."

These are inherited vulnerabilities written into your DNA.

And you could be walking around completely unaware that you're carrying them.

Here's the Brutal Truth About Your "Family Curse"

Let's be very direct:

Cancer that "runs in families" isn't some mystical curse or divine punishment.

It's genetics. Pure biology. Inherited mutations in specific genes that control cell growth and division.

And here's what makes this particularly difficult to face:

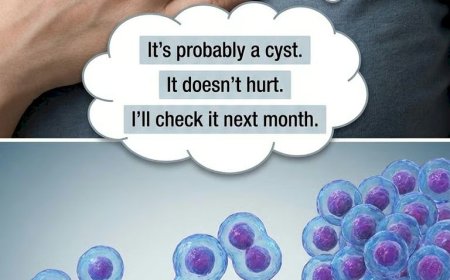

You can't feel genetic mutations.

They don't hurt. They don't cause symptoms. They sit silently in your DNA from the moment you're born, waiting for the right trigger — a second mutation, environmental exposure, age, hormonal changes — to activate.

The Two Types of Genes That Control Your Cancer Destiny

Think of your cells as vehicles with two critical systems:

1. Oncogenes: The Gas Pedal

Normal oncogenes (called proto-oncogenes when healthy) tell cells when to grow and divide. They're the accelerator.

When they mutate, they can become locked in the "ON" position.

Like a gas pedal stuck to the floor, mutated oncogenes may cause cells to grow uncontrollably — dividing endlessly and ignoring stop signals.

Common oncogenes that have been identified in cancer include RAS genes (found mutated in roughly 30% of all cancers), MYC (associated with aggressive cell growth), HER2 (relevant in some breast cancers and now targetable with specific therapies), and BCR-ABL (the molecular driver of chronic myeloid leukemia).

2. Tumor Suppressor Genes: The Brakes

These genes are your cellular brakes. They stop damaged cells from dividing, help repair DNA mistakes, and trigger programmed cell death — known as apoptosis — when repair isn't possible.

When tumor suppressor genes mutate, you lose those brakes.

Cells with DNA damage that should have been destroyed may continue to live, multiply, and accumulate further mutations.

Critical tumor suppressor genes include TP53 (mutated in over 50% of all human cancers, widely called "the guardian of the genome"), BRCA1 and BRCA2 (associated with breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers), APC (colon cancer), RB1 (retinoblastoma and other cancers), and PTEN (associated with several cancer types).

Why Your Brain Is Telling You "I Don't Need Genetic Testing"

Let's explore why you may be so effective at avoiding this information.

The Denial Mechanism

Your brain is protecting you from frightening information by producing thoughts like: "Cancer hasn't affected me yet." "I don't want to know — what's the point of worrying?" "Even if I have the gene, I might never get cancer." "My cousin got cancer at 35, but I'm only 32 — I have time."

Every single one of these thoughts is your mind shielding you from fear.

And every single one could cost you precious years.

The "Not Me" Fallacy

If you have a first-degree relative — parent, sibling, or child — with cancer, your risk is already elevated compared to the general population.

If you have multiple relatives with cancer, especially the same type of cancer, cancers diagnosed at young ages (under 50), multiple primary cancers in one person, or cancer across multiple generations, you may be in the high-risk genetic category whether you acknowledge it or not.

Pretending you're the exception doesn't change your DNA.

The Silent Inheritance: What's Actually Happening in Your Cells Right Now

Scenario 1: You Inherited One Mutated Copy of a Tumor Suppressor Gene

Let's say you inherited a mutated BRCA1 gene from your mother.

At birth, every cell in your body carries one broken BRCA1 gene. You still have one working copy from your father. You feel completely normal.

Through your twenties and thirties, you're living your life. Your cells are dividing normally. The working BRCA1 copy is doing its job — repairing DNA damage. You have no symptoms.

Then comes the critical moment: in one breast cell, the second BRCA1 copy sustains a mutation. Random chance. Environmental exposure. The accumulated cost of cellular aging. Now that single cell has no functional BRCA1 gene. It can't repair DNA damage properly. Mutations accumulate. Within months to years, that cell may become cancerous.

This is called the "two-hit hypothesis."

In this scenario, you were born one mutation away from cancer in every cell of your body.

Scenario 2: You Inherited a Mutated Oncogene

Some inherited cancer syndromes involve activated oncogenes rather than disabled tumor suppressors.

In these cases, cells may be predisposed to grow excessively from birth. Additional mutations accumulate faster. Cancers develop at younger ages. Multiple tumors are more common.

Real Stories That Illustrate the Stakes

Story #1: The Family That Ignored the Pattern

Anjali's family history included ovarian cancer in her grandmother, breast cancer in her mother and two aunts. Anjali, at 28, felt fine. "I'm young. I'm healthy. I eat well. I'll worry about this when I'm older."

At 33, she found a lump. Stage 2 breast cancer. During treatment, she finally got genetic testing: BRCA1 mutation positive.

Her reflection: "I watched three women in my family get cancer. The pattern was clear. And I ignored it because I was scared of what testing might show. If I'd tested at 25, I could have done surveillance. Caught it at Stage 0. Maybe avoided chemotherapy entirely. My fear of knowing almost cost me my life."

Story #2: The Man Who Tested Early

Rahul's father died of colon cancer at 52. His paternal uncle had colon cancer at 48. At 30, Rahul insisted on genetic testing despite his doctor initially suggesting he was too young to worry.

Result: Lynch syndrome (mutated MSH2 gene).

Actions taken: annual colonoscopies starting at 32. At 38, a colonoscopy found three precancerous polyps — all removed before they could become invasive cancer. He is now 45 and cancer-free.

His words: "Testing gave me power over my own body. Those polyps would have been a serious problem five years later."

The Five Dangerous Assumptions People Make About Cancer Genetics

Assumption #1: "I don't want to know — it'll just make me anxious."

Knowing your genetic status gives you power. Increased surveillance can catch cancer early when it's most curable. Preventive options exist. Your relatives can get tested and protected. You can make informed decisions about family planning.

Research consistently shows that people who receive positive genetic test results and take action report less ongoing anxiety than those who remain in uncertainty. Knowledge replaces unresolved fear with a concrete plan.

Assumption #2: "Even if I have the gene, I might never get cancer."

True — not everyone with a cancer gene mutation develops cancer. But with BRCA mutations, lifetime breast cancer risk exceeds 60%, according to the U.S. National Cancer Institute. Ovarian cancer risk with BRCA1 mutations ranges from approximately 39% to 58% depending on the mutation and study. Lynch syndrome carriers face a lifetime colorectal cancer risk that ranges from roughly 40% to 80%, varying by which specific MMR gene is involved and by sex.

These are meaningful numbers that warrant serious attention and medical guidance.

Assumption #3: "I'm healthy now, so I can test later."

The best time to test is when you're healthy.

Why? You can start surveillance before cancer develops. You can make prevention decisions without the pressure of an active diagnosis. You give your relatives time to test and protect themselves. Preventive screening is typically better covered by insurance than cancer treatment.

Testing after diagnosis helps with treatment decisions, but it forfeits the window for true prevention.

Assumption #4: "My family member got tested and was negative, so I'm fine."

Genetics doesn't work that way.

If your mother tested negative for a BRCA mutation, it means she didn't inherit it from her side — but your father's side could still carry mutations.

If your sister tested positive, you have a 50% chance of having the same mutation.

Each person's genetic inheritance is unique. Your relative's test result tells you nothing definitive about your own genetics.

Assumption #5: "I'll just deal with it if it happens."

By the time many hereditary cancers are felt as symptoms, they are already in advanced stages. Early-stage cancers caught through surveillance are vastly more treatable — and far less debilitating — than cancers discovered because they made themselves known through symptoms.

Understanding the Science: How Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressors Actually Work

Normal Cell Division: A Tightly Controlled Process

Healthy cells follow strict rules. Growth signals tell cells to divide only when appropriate. Checkpoint controls ensure the cell examines itself for DNA damage before proceeding. Repair mechanisms fix damaged DNA. Apoptosis destroys cells with unfixable damage. Senescence causes aging cells to stop dividing.

Oncogenes and tumor suppressors oversee these processes.

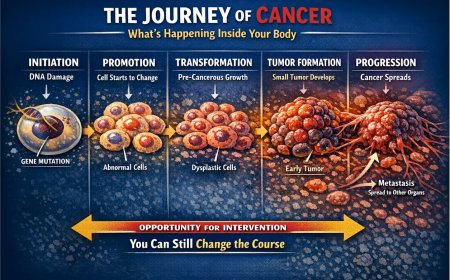

What Happens When Oncogenes Mutate

A normal proto-oncogene responds to growth signals and tells the cell to divide when conditions are appropriate.

A mutated oncogene may remain stuck in the "ON" position, constantly signaling the cell to grow even without external signals.

Result: cells may divide when they shouldn't, growth becomes uncontrolled, and cells can ignore normal limits.

The RAS gene family is a well-studied example. In a healthy cell, RAS acts like a molecular switch — on when growth is needed, off otherwise. In cancer, mutated RAS is found stuck permanently in the "on" state. RAS mutations are found in approximately 30% of all cancers, and are particularly common in pancreatic cancer (around 90%), colorectal cancer (approximately 45%), and lung cancer (approximately 30%).

What Happens When Tumor Suppressors Mutate

A healthy tumor suppressor detects DNA damage, pauses cell division, initiates repair, or — if repair is impossible — triggers cell death.

A mutated tumor suppressor may fail to do any of this. Damaged cells survive when they should have been eliminated. Mutations accumulate. Growth goes unchecked.

TP53 is the most well-studied example. Known as "the guardian of the genome," TP53 normally monitors cell health and enforces quality control. Mutations in TP53 are found in over 50% of all human cancers.

The Knudson Two-Hit Hypothesis: Why Inherited Mutations Are So Dangerous

Dr. Alfred Knudson proposed this concept in 1971 while studying retinoblastoma, a rare childhood eye cancer.

For most people without inherited mutations, cancer requires two separate random events — two "hits" — to damage both copies of a tumor suppressor gene in the same cell. This is statistically uncommon and typically takes decades. That's why sporadic cancers most often appear in older age.

For people with inherited mutations, Hit #1 is already present in every single cell at birth. Only one more random event — Hit #2 — is needed in any cell for cancer to begin. This happens at much younger ages, and multiple cancers in the same individual are more common.

This is why hereditary cancer syndromes are considered so medically significant. Carriers begin their lives one cellular accident away from cancer in every tissue.

The Major Hereditary Cancer Syndromes You Need to Know

1. Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (BRCA1 / BRCA2 Mutations)

Inheritance: One mutated copy from a parent carries a 50% transmission risk to each child.

Cancer risks with BRCA mutations: According to the National Cancer Institute, more than 60% of women who inherit a harmful BRCA1 or BRCA2 change will develop breast cancer during their lifetime. Ovarian cancer lifetime risk ranges from roughly 13% to 58% depending on which BRCA gene is affected and the specific mutation. BRCA mutations also raise the risk of pancreatic, prostate, and in some studies melanoma.

What BRCA genes normally do: they repair double-strand breaks in DNA. Without functional BRCA proteins, DNA damage accumulates — eventually leading to cancer.

Who should consider testing: multiple family members with breast cancer; breast cancer before age 50; ovarian cancer at any age; male breast cancer; Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry with family history of breast or ovarian cancer; triple-negative breast cancer diagnosis.

Updated guidelines from ASCO and the Society of Surgical Oncology (2024) now recommend that BRCA1/2 testing be offered to all patients age 65 or younger newly diagnosed with breast cancer, and to select older patients based on personal history, family history, ancestry, or eligibility for PARP inhibitor therapy.

2. Lynch Syndrome (Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer)

Genes involved: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM.

What they normally do: mismatch repair — correcting errors that occur when DNA replicates. Without them, mutations accumulate rapidly across the genome.

Cancer risks: Lynch syndrome carries a lifetime colorectal cancer risk ranging from approximately 40% to 80%, varying significantly by which MMR gene is mutated and by sex (men generally face higher risk than women). Women with Lynch syndrome also face a lifetime endometrial cancer risk of up to 60% for MLH1 and MSH2 mutations. Additional elevated risks include ovarian, gastric, small intestine, pancreatic, urinary tract, and brain cancers.

Who should consider testing: colorectal or endometrial cancer before age 50; multiple relatives with colon or endometrial cancer; multiple primary cancers in one person; a family history consistent with a hereditary pattern.

Current clinical guidelines from NSGC, ASCO, and multiple professional bodies recommend universal tumor screening for Lynch syndrome in all newly diagnosed colorectal and endometrial cancers.

3. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (TP53 Mutation)

What TP53 normally does: it serves as "guardian of the genome," detecting DNA damage, halting cell division, and initiating repair or programmed cell death.

Cancer risks: multiple cancer types, often at very young ages, including breast cancer (frequently before age 40), sarcomas of the bone and soft tissue, brain tumors, adrenal gland tumors, and leukemia.

Who should consider testing: cancer before age 30; multiple different cancers in one person; several relatives with varied cancers at young ages.

4. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP — APC Gene Mutation)

What happens: hundreds to thousands of polyps develop in the colon and rectum. Without surgical intervention, nearly 100% of individuals with classic FAP develop colorectal cancer, typically by age 40.

What APC normally does: it regulates cell growth in the intestinal lining and prevents excessive polyp formation.

Management: preventive removal of the colon (colectomy) is typically recommended in the late teens or early twenties. With surgical intervention, cancer is largely preventable.

What You Must Do in the Next 30 Days

Stop reading for a moment. Take this seriously. Here is a practical plan.

Week 1: Document Your Family Cancer History

Make a complete list of all relatives with cancer, including the type of cancer, their age at diagnosis, whether they had multiple cancers, and whether they are still living. Include parents, siblings, children, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins.

Look for meaningful patterns: the same cancer type in multiple relatives; cancer at young ages (under 50); multiple different cancers in one person; rare cancers such as ovarian, pancreatic, or male breast cancer.

Week 2: Consult a Genetic Counselor or Oncologist

Who needs genetic counseling: anyone with multiple relatives with the same cancer; cancer diagnosed at young ages in the family; a known genetic mutation already identified in a family member; a personal history of cancer before age 50; Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry with breast or ovarian cancer in the family; or any man in the family diagnosed with breast cancer.

What to expect from genetic counseling: a thorough review of family history, an assessment of cancer risk, a discussion of available testing options, interpretation of results, and individualized management recommendations. Genetic counseling should ideally occur both before and after testing.

Weeks 3–4: Get Tested If Recommended

Types of genetic tests include single gene testing (targeting one specific mutation), panel testing (examining multiple cancer-relevant genes simultaneously), and tumor testing (if you already have cancer, testing the tumor can guide both understanding and treatment).

Where to get tested in India: major cancer centres (Tata Memorial Hospital, AIIMS, Apollo Hospitals, Fortis Healthcare), and specialized genetic testing laboratories such as MedGenome, Strand Life Sciences, and SRL Diagnostics.

What the process involves: typically a blood draw or saliva sample, results in 2–6 weeks, and follow-up counseling to interpret results and discuss next steps.

If You Test Positive: Your Action Plan

Finding out you carry a cancer gene mutation is not a death sentence. It is information — powerful, actionable information — that can protect your life.

For BRCA Mutations:

High-risk screening protocol typically includes breast MRI and mammogram every 6–12 months starting around age 25–30. Depending on individual circumstances and consultation with specialists, some women consider preventive mastectomy, which evidence shows can reduce breast cancer risk by over 90%. Discussion of preventive removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes after childbearing is also recommended — this option has been shown to dramatically reduce ovarian cancer risk in BRCA carriers.

Notably, Angelina Jolie publicly disclosed her BRCA1 mutation and decision to undergo preventive surgery, helping raise global awareness about genetic cancer risk and the options available to carriers.

For Lynch Syndrome:

High-risk screening typically includes colonoscopy every 1–2 years starting around age 20–25, or earlier depending on family history. For women, annual endometrial biopsy is commonly recommended starting around age 30–35. Some women with Lynch syndrome, after completing their families, consider preventive hysterectomy in consultation with their physicians.

Regular colonoscopy has been shown to be highly effective: catching and removing precancerous polyps before they become invasive cancer is central to Lynch syndrome management, and five-year survival rates among Lynch syndrome patients who develop colorectal cancer are reported at approximately 94% when cancer is found and treated.

For Li-Fraumeni Syndrome:

Comprehensive surveillance typically includes whole-body MRI annually, brain MRI annually, breast MRI every 6 months for women, regular blood tests, and dermatological examinations.

For All Hereditary Cancer Syndromes:

Tell your relatives. Your siblings carry a 50% chance of having the same mutation. Your children carry a 50% chance. Your cousins, aunts, and uncles may also be at risk. Testing can save their lives.

Updated ACS and Professional Guidelines on Screening and Self-Awareness

The American Cancer Society and other professional bodies continue to evolve their guidance on hereditary cancer screening. Current guidelines from the ACS support awareness of changes in one's body and prompt reporting of symptoms to a physician. For high-risk individuals — including known BRCA mutation carriers — the ACS supports annual MRI in addition to mammography beginning around age 30, rather than mammography alone. For colon cancer, the ACS continues to recommend that all adults at average risk begin colorectal cancer screening at age 45; those with Lynch syndrome or other hereditary syndromes should begin significantly earlier, typically in their early twenties.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology's 2024 guidelines specifically expand germline genetic testing recommendations to all breast cancer patients diagnosed at age 65 or younger, broadening access significantly beyond earlier criteria that required a family history component.

All of these guidelines underscore one consistent message: those with a meaningful family history of cancer should not wait for personal symptoms to prompt action. Proactive assessment with a genetic counselor is the appropriate first step.

The Psychological Battle: Fear Versus Empowerment

"If I test positive, I'll live in constant fear."

The reality is more nuanced. People who test positive and engage with a clear management plan consistently report that structured knowledge replaces the diffuse, unresolved anxiety of uncertainty. Having a plan — specific screening dates, a medical team, and clear next steps — is demonstrably different from the helpless dread of an unknown threat. Living with uncertainty while watching family members fall ill often carries its own, quieter form of ongoing anxiety.

"I'd rather not know and just live my life."

Not knowing doesn't prevent cancer. It delays detection. The difference between Stage 0 and Stage 3 is not just medical — it is the difference between weeks of treatment and years of it. Between manageable intervention and life-altering consequences.

"What if my family judges me for getting tested?"

Your life has value independent of others' comfort. When you test positive and inform close relatives so they can protect themselves, you are doing something genuinely meaningful. Most people, when they understand what you did and why, are grateful.

Oncogenes vs. Tumor Suppressors: A Reference Comparison

| Aspect | Oncogenes | Tumor Suppressor Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Normal function | Promote controlled cell growth | Inhibit cell growth; trigger repair or death |

| Analogy | Gas pedal | Brakes |

| Mutation type | Gain of function (overactive) | Loss of function (underactive) |

| Inheritance pattern | Rare to inherit mutated oncogenes directly | Common to inherit one mutated copy |

| Mutations required for cancer | One hit (dominant effect) | Two hits (both copies must be lost) |

| Examples | RAS, MYC, HER2, BCR-ABL | TP53, BRCA1/2, APC, RB1, PTEN |

| Result when mutated | Excessive, inappropriate growth signals | Loss of growth control and cellular oversight |

What Genetic Testing Cannot Tell You — And Why That's Acceptable

Testing can tell you whether you carry a known high-risk mutation, your approximate lifetime cancer risk based on population data, what type of surveillance or prevention may be appropriate for you, and which relatives should consider testing.

Testing cannot tell you exactly when or whether you will develop cancer, your precise individual risk (results reflect population averages, not individual certainty), whether specific environmental exposures will matter for you, or every possible genetic risk (the science of cancer genetics continues to evolve rapidly).

But even imperfect information is meaningfully better than no information. A BRCA-positive person following a surveillance protocol has dramatically better outcomes than someone who ignores their family history and is eventually diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Special Considerations for Indian Families

There are cultural dimensions worth addressing directly.

The belief that "if it's meant to happen, it will happen" is understandable. But medical science offers tools that genuinely alter outcomes. Using them is not about fighting fate — it is about being informed.

Privacy concerns are real. Testing results do not need to be disclosed broadly. You can share findings only with close relatives who would benefit from testing themselves.

Complementary and traditional medicine systems play an important role in wellness for many people. However, no herbal, Ayurvedic, or alternative treatment has been shown to correct a germline genetic mutation. Surveillance and prevention through evidence-based medicine remain the standard of care.

Marriage concerns are legitimate in a sociocultural sense, but worth examining: a partner who rejects someone for proactively protecting their health is communicating something important about their values. Genetic knowledge also protects future children, who may themselves be at risk.

Professional Support Options

If you're experiencing possible cancer symptoms, seeking a second opinion, or unsure which tests or treatments are right for you, don't wait. Speak with a qualified oncologist today.

Connect with experienced U.S.-based cancer specialists for a comprehensive second-opinion consultation. They will carefully review your case and help determine the most appropriate next steps for your individual health needs:

👉 https://myamericandoctor.com/our-doctors/

You may also choose to enroll in our upcoming concierge medical clinic in India, Global Concierge Doctors. We offer U.S.-style primary care with 24/7 access to India-based physicians for ongoing guidance on any health concern. When required, we coordinate referrals to trusted specialists in India and the U.S. for advanced evaluation and care.

Your health decisions today shape your life tomorrow.

The Final Word: Your Genes Are Carrying Your Family's History

Your DNA carries the accumulated biological history of every generation before you. The cancers that affected your grandmother, your uncle, your cousin — they began at the molecular level, in genes that you may have also inherited.

You might carry mutations that give you information others in your family never had. Early warning. Time to act. Time to screen. Time to prevent.

You can ignore this. You can tell yourself the pattern isn't real. You can decide you are the exception.

But every day of delay is a day that matters if those mutations are present and active.

Your grandmother didn't have genetic testing. She couldn't know. She couldn't prevent.

You can.

The question is: will you?

Take Action Now

This week, write down your complete family cancer history. Contact a genetic counselor or oncologist for a consultation. Ask your doctor about genetic testing if your history warrants it. Share this article with one close family member who may need it. If you have a known mutation in your family, schedule testing this week.

Do not wait until you are diagnosed. Do not wait until you are "old enough to worry." Do not wait until another family member is affected. Do not wait until you feel ready.

There is no perfect time to find out you carry a cancer gene mutation.

But there is a right time to act on that information: before cancer develops.

Your life is written in your genes. The question is whether you will read the warning before it becomes the diagnosis.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is provided strictly for educational, informational, and awareness purposes only. It is not intended to be, and should not be construed as, professional medical advice, diagnosis, treatment, or a substitute for consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

No Doctor-Patient Relationship

The information presented in this article does not establish a doctor-patient relationship between the reader and the author, publisher, or any affiliated entities. No medical decisions should be made based solely on the content of this article.

Consult Qualified Medical Professionals

If you are experiencing any symptoms mentioned in this article, have a family history of cancer, have been diagnosed with cancer, are considering genetic testing, or have concerns about cancer risk, seek immediate consultation with qualified oncologists, genetic counselors, physicians, or appropriate medical specialists. For medical emergencies, contact emergency services immediately.

Individual Medical Situations Vary

Every person's medical condition, health history, family history, genetic profile, risk factors, cancer type, and circumstances are unique. Diagnostic tests, genetic testing, treatment options, and medical recommendations must be tailored to individual patients through direct consultation with licensed healthcare providers who have access to complete medical histories and can perform proper clinical evaluations.

Not a Recommendation for Specific Tests or Treatments

References to genetic testing, BRCA testing, Lynch syndrome testing, tumor marker tests, biopsies, imaging studies (CT scans, PET scans, MRI), blood tests, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, preventive surgeries (mastectomy, oophorectomy, colectomy), surveillance protocols, or any other diagnostic procedures and treatments in this article are for informational purposes only and do not constitute recommendations that you should or should not undergo these tests or treatments. All decisions regarding genetic testing, medical testing, diagnosis, prevention strategies, and treatment should be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals based on your specific medical situation.

No Guarantee of Accuracy or Completeness

While efforts have been made to provide accurate information, medical knowledge continuously evolves, particularly in the rapidly advancing fields of oncology and cancer genetics. The information in this article may not reflect the most current research, clinical guidelines, genetic testing protocols, treatment options, or medical practices. The author and publisher make no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the content.

Do Not Disregard or Delay Professional Medical Advice

Never disregard, avoid, or delay obtaining professional medical advice from qualified healthcare providers because of something you have read in this article. If you have questions or concerns about information presented here, discuss them with your personal physician, oncologist, or genetic counselor.

Third-Party Resources and Links

Any references to third-party medical services, genetic testing laboratories, clinics, doctors, cancer centers, genetic counseling services, or external websites are provided for informational purposes only and do not constitute endorsements. The author and publisher are not responsible for the content, services, or practices of any third-party entities.

Limitation of Liability

To the fullest extent permitted by law, the author, publisher, and affiliated entities disclaim all liability for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, or punitive damages arising from the use of, or reliance on, information contained in this article. This includes, but is not limited to, medical complications, genetic testing decisions, treatment decisions, preventive surgery decisions, financial losses, or any other adverse outcomes.

Geographic and Regulatory Considerations

Medical regulations, standards of care, availability of genetic testing, availability of diagnostic tests, treatment protocols, and access to cancer therapies vary by country, region, and healthcare system.

Genetic Testing Considerations

Genetic testing has benefits, limitations, and potential psychological impacts. Test results may have implications for family members, insurance coverage, employment, and emotional well-being. Genetic counseling before and after testing is strongly recommended. Not all genetic mutations are well understood, and testing may reveal variants of uncertain significance.

Clinical Trials and Experimental Treatments

Any references to clinical trials, experimental treatments, or investigational therapies are for informational purposes only. Participation in clinical trials should only be considered after thorough discussion with your oncology team and a full understanding of all risks and benefits.

Your Responsibility

You acknowledge that you are solely responsible for your own health decisions and that you will consult with appropriate licensed healthcare professionals before making any medical decisions, undergoing genetic testing, or beginning any treatments.

Acknowledgment

By reading and using the information in this article, you acknowledge that you have read, understood, and agreed to this disclaimer in its entirety. You further acknowledge that this article has been created with the assistance of artificial intelligence. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, AI-generated content may occasionally contain errors, omissions, or inaccuracies. The information presented here is intended solely for educational and informational purposes and should not be relied upon as a substitute for professional medical advice. Readers are strongly encouraged to consult qualified healthcare professionals, refer to peer-reviewed medical literature, and cross-reference information from established clinical sources before making any health-related decisions.

Last Updated: 4th February 2026

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0